A Futuristic Theology

- Mikel J. Wisler

- Dec 22, 2016

- 6 min read

What happens when long-held dogma collides with hard empirical data?

"The alien entered the chapel just as Father Wickham was reciting the Doxology." So opens "Sanctuary," a novella by Michael A. Burstein.[1] An insect-like alien seeks sanctuary within the walls of a Catholic chapel aboard a space station. The fictional priest is forced to confront moral and theological questions as this alien seeks refuge after violating her own people's religious dogma. Father Wickham, however, is also bound by decisions made at the fictional Vatican 5, which deemed the aliens species then newly encountered by humanity to not have souls.

Sound weird? Well, Burstein's not alone in asking such questions. C. S. Lewis (of Narnia fame) posed his own theologically speculative questions in fictional form in his “Ransom Trilogy,” along with others works. Out of the Silent Planet, the first book in the “Ransom Trilogy,” tackles head-on what might happen if our theology is confronted with intelligent alien life. Lewis, a former atheist, thought a lot about the developments of science and the interplay they had with faith. In an essay titled "Religion and Rocketry"[2] Lewis reflected, "When the popular hubbub has subsided and the novelty has been chewed over by real theologians, real scientists and real philosophers, both sides find themselves pretty much where they were before." The essay is short but packs a lot of insight on Lewis’ part in terms of presenting a flexible theology that refuses to take any hard stance on the spiritual nature of an intelligent alien species until such a species is actually encountered. For Lewis, our current theology is just not set up to deal with aliens and we can’t expect that it will even apply to other life forms in the universe. But this doesn’t stop Lewis from at least exploring the idea and presenting some much needed caution and restraint. He seems down right confident that if humanity should be the ones to happen upon other intelligent life in the universe, we will not treat such aliens well. Why does he say this? Because the track record humanity has when it comes to explorers encountering indigenous peoples is pretty horrendous. Because of this, he writes:

What I do know is that here and now, as our only possible practical preparation for such a meeting, you and I should resolve to stand firm against all exploitation and all theological imperialism. It will not be fun. We shall be called traitors to our own species. … We shall probably fail, but let us go down fighting for the right side. Our loyalty is due not to our species but to God. Those who are, or can become, His sons, are our real brothers even if they have shells or tusks. It is spiritual, not biological kinship that counts.[3]

Okay, that’s all quite interesting in an abstract sort of way, but we’re still no nearer to discovering intelligent alien life than we were when Lewis wrote his essay in 1958 (thus the gender bias in his language). But science has a history of marching forward and clashing with religious ideas that at one point seemed paramount. Galileo Galilei’s trial remains a primary example.[4] But that was a long time ago. Today, there are strong voices within the broad array of Christian traditions that continue to insist (in spite of overwhelming biological evidence to the contrary, I’d suggest) on a literal reading of the first two chapters of Genesis. Some Christian colleges have elevated this view to an institutional dogma, which staff must profess in order to work at such schools. My alma matter took this approach just last year, resulting in the resignation of Dr. Jim Stump, whom I had the privilege of studying philosophy under.[5] While I may not agree with what my old college decided to do, they certainly have the right to run their institution in the means they deem most fitting. But it doesn’t strike me as forward progress or even a helpful approach. Why is it necessary to take up any position? Why not allow it to be an area of healthy academic and spiritual debate?

C. S. Lewis concludes “Religion and Rocketry” by pointing out that, “What we believe always remains intellectually possible; it never becomes intellectually compulsive. I have an idea that when this ceases to be so, the world will be ending.”[6] This is a far more open-ended approach than the one my former college has taken up. Nevertheless, such a position of dead-set "certainty" is now, in any practical sense, an institutional dogma for them. Because of this, I’ve found myself wondering about something with potentially broad-reaching implications: is our theology flexible enough to even survive a scientifically mature future? What I mean by this is: do we have the theological imagination and creativity necessary to foresee a world very different than our current one?

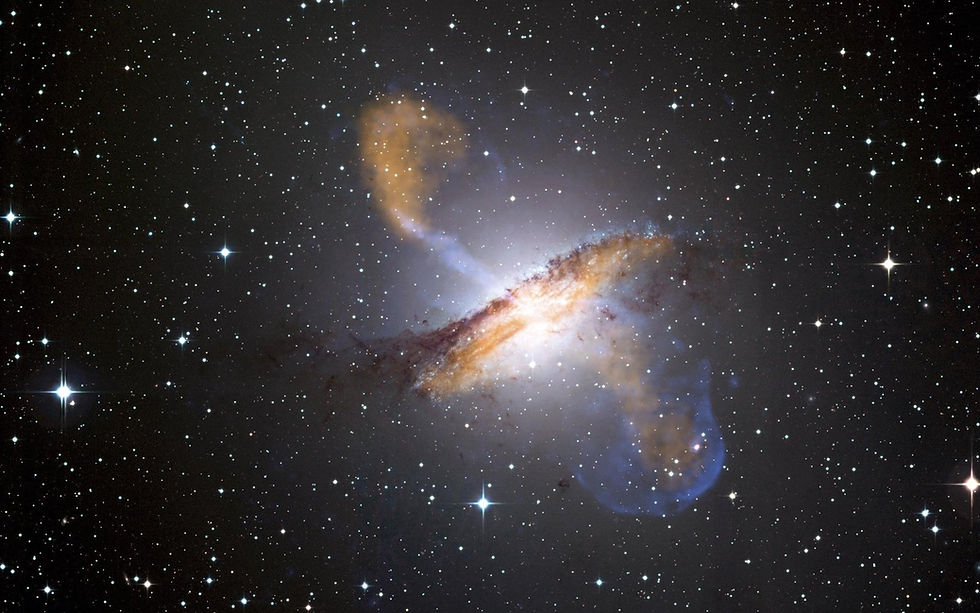

What happens when NASA announces conclusive evidence of living organisms in the frozen oceans and theorized hot springs of Europa (one of Jupiter’s moons) or in the briny waters recently discovered on Mars? For some, this discovery might well shake their faith if their theology insists on the specialness of life on Earth alone. But this is only one of the next likely steps in our ever-expanding scientific knowledge. The crucial question as I see is: as people of faith, are we ready for the next mind-bending scientific discovery, or are we potentially too dogmatic about things that don't necessarily help us actually move closer to Jesus? Are we ready to embrace the needed imagination to envision a future where string theory offers us conclusive evidence of parallel universes? Can we envision how even in that world we might see and appreciate how God is active and reaching out to us?

Alright,[7] why do I care about these far-fetched ideas (aside from being a sci-fi writer)? I have what I think is a profoundly practical answer: I believe a more creative, forward thinking, flexible theology is essential in allowing more room for healthy discussion and divergent perspectives within faith communities. Speaking as someone who nearly abandoned faith just after graduating from a Christian college, it seems to me that at least in part it has been the religious world’s tendency towards inflexible dogmas and doctrines that are responsible for repelling young, intellectually curious people from our churches. Modern Christian theology has had a strong focus on systems of belief and apologetics, fostering a fixation on holding the “right set of beliefs,” (which vary wildly depending on which tradition one happens to hail from). The result is that there's little room left for genuine discovery and new knowledge. Modernist Christianity has asked its disciples to essentially stop questioning and stand still. Belief became a static position, not the launch pad for the journey it actually is.

Don’t get me wrong; it's an understandable impulse. We’re all change averse. And yet, change is inevitable. This leads me to the deep suspicion that the only truly viable future for the Church (as a whole) is to embrace the larger journey of discovery the human race is already on. Honestly, if I were not in such an open faith community now, opting out of church altogether would feel like the only sensible choice. Thankfully, there's a third option. We can learn from Lewis’ “wait and see” attitude. We can allow room for God to be bigger than our theological constructs and current scientific understanding while still embracing the growth of empirical knowledge and humanity’s thirst for spiritual meaning. But, to do this, we’ll need a lot more flexibility and creativity.

[1] Published in the September 2005 issue of Analog Science Fiction and Fact.

[2] Included in the book, The World's Last Night: And Other Essays.

[3] “Religion and Rocketry”, The World's Last Night: And Other Essays, pgs 90-91.

[4] We can cut the Catholic Church some slack here if we keep in mind that most people, religious or not, we not ready for the Earth to not be the center of the universe at that time.

[5] For more on that, I recommend this article from Christianity Today: http://www.christiantoday.com/article/professor.at.christian.college.resigns.after.it.insists.on.anti.evolution.statement/58901.htm

[6] “Religion and Rocketry”, The World's Last Night: And Other Essays, pg 92.

[7] For the sake of grammatical illustration, I’ve chosen to use “alright” as one word since it is not yet officially recognized as a single word, but likely will be in the future just as “altogether” and “already” are now. See: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/usage/all-right-or-alright

Comments